Siya Khumalo on God and queerness: The Mamba Interview

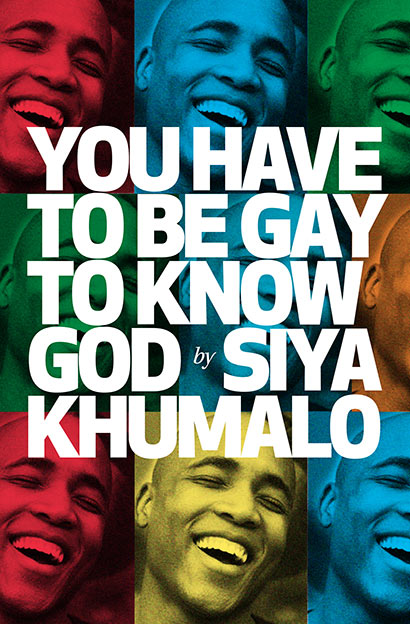

It’s not every writer that has the foreword to their debut book written by none other than Constitutional Court Justice Edwin Cameron. This alone gives some indication of the significance of Siya Khumalo’s new book, provocatively titled You Have To Be Gay To Know God.

It’s not every writer that has the foreword to their debut book written by none other than Constitutional Court Justice Edwin Cameron. This alone gives some indication of the significance of Siya Khumalo’s new book, provocatively titled You Have To Be Gay To Know God.

The book brings together Khumalo’s informed and challenging commentary on the subjects of religion, politics, power, patriarchy and sex – and how these hot button topics are inextricably intertwined. He explores these themes through an accessible biographical narrative; his own black, African, queer and also universally human experiences. And he does it with wit and humour.

At the age of 31, the Durban-born and bred Khumalo’s life has included a stint in the military and as a contestant in both Mr Gay South Africa and Mr Gay World 2015 (representing Zambia, thanks to a familial connection). He was also a Mambaonline.com Sexiest Man of the Year finalist. Through all this he’s shown a commitment to affirming LGBTQ experiences, and teasing out social, spiritual, political and other truths about queer life in South Africa.

His blog postings have drawn widespread attention and he is often interviewed on radio and on media platforms for his controversial take on current affairs. He writes regularly for Daily Maverick and other publications, probing a wide range of issues, and creates content for business (we all have to pay the bills).

Mambaonline recently sat down with Khumalo to talk about his book and the kind of response he’s received.

Mambaonline: That title, You Have To Be Gay To Know God, is quite provocative. Talk to me about being gay and Christian.

Khumalo: I do believe there is a God. I also believe that nothing in all of the universe has to be anything other than what it is to be acceptable to God, otherwise why would God have put it there? If he wanted it different, then he would have made it different. So I’m gay and a lot of people think that being gay is an abomination before God, and I’m like, “then I wouldn’t be gay, I would have been something else.” Who creates something, then hates it?

When did you start writing the book?

I started writing the book in 2013, because there were a lot of hate crimes against gay people. Call them punitive or corrective rapes, murders, lots of persecutions, and most of the discussions that I was seeing online were about how being gay is a sin. So there would be a murder or a rape and the response would be “ah, but is it a sin or is it not sin?” and I would think, “guys, there’s been a rape, there has been a murder so how is this the conversation we’re having now?” So I started questioning a lot of the assumptions that inform mainstream Christian theology.

The book is part biography, part social, religious and political analysis, and a manifesto of sorts…

It was meant to be a nice, polite book for Christians about the Bible. I write Bible commentary when I’m bored; which, I guess, is one way to pass the time. It was me sharing with a lot of Christians that these are the issues that are coming up today. It was very difficult to pass that on to any publisher but I found a publisher who suggested that I write about how I arrived at these beliefs in the course of my life. And if I was willing to write and get naked, as it were, then I might have a stronger book. I also put in some of the socio-economic commentary from my blog. So the book became a kind of soup, but with a thread running through it. The thread is, we have to become self-aware; we have to face our shadows, we have to face our demons. We have to become aware of the choices we are making and the ramifications of the world we live in.

How difficult was it to bring in a biographical aspect to the book?

Well it’s tricky, because there is lots of admin involved. You start writing about something that happened and you’re not sure if you’re recalling it correctly and then you have to check it with the people who were involved. Also, you don’t know how much is too much. I thought the guy Daniel, in the book, would cringe at some of the sex scenes that I wrote. I sent him that part of the manuscript and he said if I thought it was okay with it, then he was also fine with it. So, it was also just about people’s privacy and ethics. Also, just remembering things; and it’s not just a technical memory problem but it’s also an emotional memory problem where going back somewhere might hurt so much that your mind reminds you to not go back there.

Did you write this book for LGBTQ people of faith?

Did you write this book for LGBTQ people of faith?

More for the detractors, but it seems to be benefiting people of faith more, because the detractors have made up their minds that they’re not reading the book. So if [queer] people of faith are being enriched by this then I am very glad that they feel more at home again with the universe.

Where did the need to question religion and how it intersects with your sexuality come from?

It was important for me to find meaning in where I come from, where I am going to and whether I am connected or not, and that’s where the religious wrestling came in. Faith or religion gives a language or gives symbols that you can use to orient yourself in what you can’t see, because that’s all symbols can do; they tell you what you otherwise have no idea about. It’s only when you interact with them, you kind of figure out a language where you fit into the invisible and unseen scheme of things.

How do we as LGBTQ people find meaning in organised religion? If it does not welcome us, should we not be breaking away from it?

I believe in beating the devil at his own game. I do believe that we should not retreat from the battlefield until our haters choose to run. The majority of homophobic rhetoric comes from this book [the Bible]. I will not spend eternity worshipping that book; human beings sat down and they wrote that book. Had it fallen from the sky then we’d be having a different discussion right now.

In the book you jump from having a religious debate to pretty explicitly, and quite beautifully, describing having sex with another man. Why did you decide to do that?

Why the religious is so close to the sexual is because from very early on in some of our religious texts, it’s shown that the split between human consciousness and the rest of the universe was most profoundly seen in our attitudes towards sexuality. One day we played a very dangerous game, and that game was called “judgement”, and we judged and became ashamed (that is Adam and Eve in Genesis). The reason why we all now wear clothes is because we’re all walking around cut off, mentally and spiritually, from the whole, and sex is a point of redemption. It’s one of the places where redemption plays out. Like Christ being crucified naked on the cross is a picture of sex, that’s why we call it passion. Our sexuality is the physical manifestation of what is true in the unseen. It really does not serve us to pretend like there isn’t a connection.

Did you have any concerns about writing about something so explicit?

Yes, when my family said they couldn’t wait to read my book, I told them that I was going to give them a censored version. (Laughs) But it [writing the book] had to be done. It was quite high stakes for me, but the principal of doing it properly still applied, and I can’t lie about the fact that sex is a physical and concrete metaphor for all the issues we have, mentally and spiritually.

Why did you decide to go into the military, when many would assume it to be a hostile place for someone who is LGBTQ?

It was quite a welcoming space actually, from my experience. The people there are also people but they just happen to wear uniforms. When I left high school, I did not understand any of the career paths that were being laid out before me. It was a case of lack of exposure to these careers, unlike my racial counterparts; so, for instance, mom is an accountant and dad is an engineer. For me this was not there, yet the need to throw myself into my beliefs was there. At the time, the military and the people I had met from the military were the only contact I had with people who believed in the sovereignty of this country. It was a starting point I felt comfortable with. I saw it as an adventure and also as one way in which I could find that “aha moment” to figure out the meaning of life.

Your book also looks at patriarchy and rape culture…

Rape culture is not an aberration in heterosexism, it is manifestation of what heterosexism does, when it is left to its own device and there is no other alternative. It’s what happens when men, are considered to be men only when they’re around women and vice versa. Then this entitlement of, “I am incomplete without you, so how dare you withhold your affection and sex from me” develops. The LGBTQ community has been there, trying to tell heterosexuals that this can’t be the only way relationships exist. Heterosexism formed hierarchies that excluded us as the LGBTQ community, so how can we fix the world? We can only come in if you are prepared to dismantle heterosexism. But this is not to say that there aren’t hierarchies in LGBTQ relationships.

Tell us about the response you’ve received to the book?

Tell us about the response you’ve received to the book?

Are people actually seeking you out online to attack you?

Yes they do. They usually quote Bible verses about homosexuality, mainly from the New International Version, which I think there was a bit of a mistranslation there. But I’m happy we have translation issues, because a mistranslation is a great time to pick up your own blind spots and biases. This is why I also don’t think of it as a mistranslation; because that implies someone made a mistake, when it was deliberate. It was a political decision, which is why I write about religion, politics and sex. I argue that they are the same thing. A lot of Christians think that Christianity is innocent. It’s so difficult to say to them, “Listen, part of your spiritual journey is stripping the facade of the innocence of your own faith and seeing it as a tool that has really served the interest of the most powerful.” A lot of devout Christians have no interest in wrestling with truth, which is ironic right?

Siya Khumalo’s You Have To Be Gay To Know God is published by Kwela and sells for around R255. Watch a video of our interview below.

- Facebook Messenger

- Total106

Leave a Reply