How a gender conspiracy theory is spreading across the world

Transgender and gender-fluid people are the victims of a growing gender conspiracy theory (stock image)

Gender identity cannot be fluid, according to the Catholic church. Its first extensive document on so-called “gender ideology”, published in June 2019, stated that there are only two genders which are constituted biologically and cannot be “individually chosen”. It also warned that flexible ideas about gender may pose a threat to traditional Catholic values.

Even though many Catholics were concerned about the document’s potential to promote transphobia and homophobia, it resonated with many people’s fears of what we can call a gender conspiracy. This is a broader conviction that gender theory and gender studies represent an ideology that is a threat to society – an idea that is becoming increasingly widespread across the world.

Our new research gives insights into this conspiracy theory and how it relates to religion. It is based on a survey from Poland, where there’s plenty of support for the conspiracy theory and the Roman Catholic church holds a strong position. Right now, there’s even a debate about whether the coronavirus pandemic is a punishment for gender theory.

People who believe in the gender conspiracy theory think that a gender ideology is a secret plot by powerful people to hurt their in-group – for example, the Catholic church. This is in fact how most conspiracy theories work. In line with this reasoning, academics and activists who emphasise that gender is not only a biological phenomenon, but also a psychological one, are seen as enemies of human nature.

Together with feminists and the broader LGBTQ movement, they are perceived as strategically and purposefully seeking to deny the importance of the traditional differentiation of men and women. This alleged denial has been blamed for triggering conflict between the sexes. Proponents of the conspiracy theory also believe that it is destroying the family unit, which is one of the most important values for Catholics.

While researchers aren’t entirely sure where and how this conspiracy theory started, the view has now spread across the world. Dariusz Oko — a Catholic priest and a professor at the Pontifical University of John Paul II in Poland — has presented some of the most extreme opinions on the matter. According to him, “genderists like to act secretly, in silence, like a mafia. They want to do their revolution top-down, by taking the centres of power and the media. They prey on citizens’ ignorance to bypass democratic procedures and forcefully impose their ideologies”.

Barbara Rosenkranz, an Austrian politician, has also expressed conspiratorial claims about gender. She has warned against a totalitarian conspiracy of gender activists that allegedly aim to create a new type of human being – “a genderless person”. She has argued such plans are pursued secretly by an “elite” blinded by ideology, ignorant of the laws of nature and tradition.

Similar views were voiced by Michel Schooyans, a Belgian priest in his 2001 book entitled The Hidden Face of the United Nation. They have also been backed by representatives of the La Manif Pour Tous movement in France, which claims to defend the “traditional family”.

All of these authors, activists and religious officials seem to put forward similar messages, which are typical for conspiracy theories in general. One is to warn people of the threats posed by gender theory, which allegedly aims to secretly destroy the Catholic church. The other is that they promote actions to stop the conspiring enemies from executing their nefarious plan, such as banning sex education in schools.

The idea of “Gayropa,” used in Russia pejoratively to refer to Western ideas about gender and Russia’s special role in resisting them, comes with similar messages.

Religion v threat

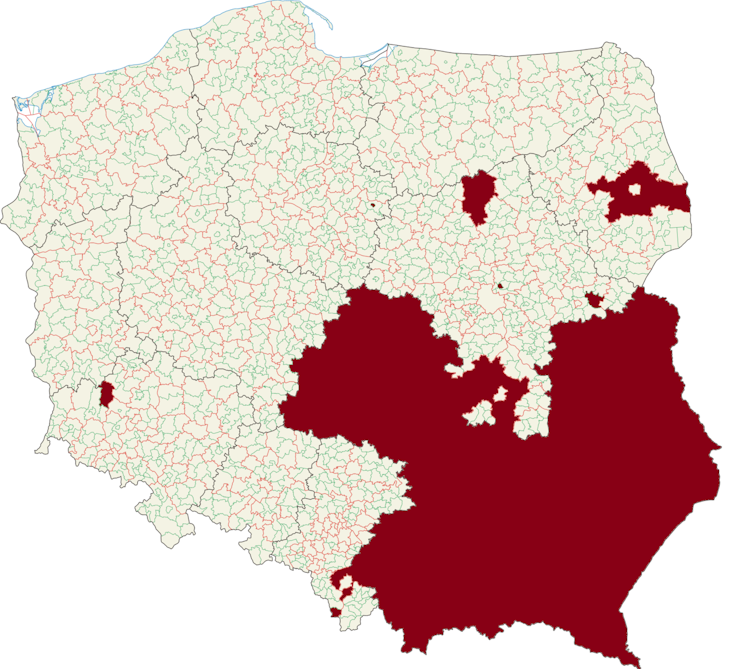

Poland is a country where political parties often warn voters of gender ideology. It is no wonder that the gender conspiracy theory has really taken hold there. And it is having real effects. Recently, “LGBT ideology-free zones” were declared by local governments in certain areas of Poland. While this is symbolic rather than enforceable, it illustrates just how dangerous such ideas can be.

wikipedia, CC BY-SA

In our project, we conducted a survey with a nationally representative sample of more than 1,000 people. We found that around 30% of Polish Catholics believed in a gender conspiracy. This was defined as a secret plan to destroy Christian tradition partly by taking control over public media.

We also found that these beliefs were not related to the mere strength of one’s religiosity. Rather, they were stronger among those Catholics who believed that their religious group was deserving of special treatment, being chronically undermined by different groups. This suggests that gender conspiracy beliefs are not a necessary consequence of strong religious devotion. Rather, they are more likely to flourish when one’s religion is portrayed as being under threat.

We also found that “gender conspiracy beliefs” were linked to keeping a social distance from gay people, and harbouring hostile intentions towards them. For example, we found that 70% of the participants who believed in a gender conspiracy theory would not accept a gay family member.

Overall, the results of our project suggest that portraying gender studies and gender activists as a part of a conspiracy theory can have serious consequences – leading to hostility towards those who do not conform to traditional gender roles. This hostility even extends to those who simply take scientific interest in issues of gender.

So given that conspiracy theories can be so damaging, how do you stop them from spreading? Sadly, this has turned out to be incredibly difficult to figure out, as they are very hard to debunk efficiently. But we are hoping that the better we understand the details of what makes people believe in conspiracy theories, the better we will get at stopping their spread.

Article by Marta Marchlewska, Adjunct assistant professor, Head of the Political Cognition Lab, Institute of Psychology, Polish Academy of Sciences and Aleksandra Cichocka, Senior Lecturer in Political Psychology, University of Kent. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()

Leave a Reply