Art: Mourning the faceless gay victims of Isis

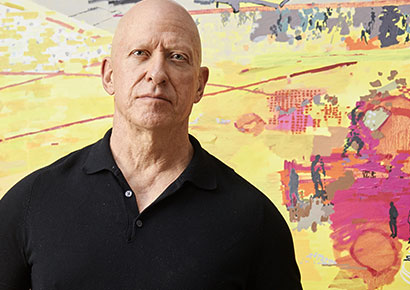

Clive van den Berg

Artist Clive van den Berg’s new exhibition, A Pile of Stones, at the Goodman Gallery in Johannesburg, is a thoughtful tribute to the dozens of gay men sadistically murdered by the Isis regime.

Since 2014, Isis in Syria and Iraq has been horrifically executing gay men and those accused of being gay. The group distributes images and videos of the brutal public killings – not only as a warning to “moral deviants” but also as a propaganda tool to frighten enemies and to attract recruits from around the world.

Most of the victims are thrown off the top of buildings. If they survive the fall, they are stoned to death by people in the crowd waiting below. The victim’s identities and stories are never revealed and their faces are usually obscured by blindfolds.

Mambaonline spoke to Van den Berg about his work, which includes freezing moments of the executions in tenderly hand-carved wood. The centrepiece of the exhibition is a three metre high wood sculpture that features both representations of the victims falling or on the ground, as well as some of the individuals in the crowds.

On seeing the images of the killings: “I couldn’t look at them for a while. I was totally shocked. After getting over the shock, I asked: ‘What do you do with this? How do you make good?’ Of course, you can’t make good, but you can give these men what was denied them by Isis, who spectacularised their death in the most gross kind of way. We can raise awareness, and we can mourn. And mourning can be an act of solidarity.”

Making the first works: “It was a difficult process partly because you have to look very hard at the images to get the detail to elicit empathy from your viewer. I used the perspective of the photographer – either from the pavements looking up or from the buildings looking down. I’ve materialised the sky [in the wood] – It’s a symbolic arresting of the fall. I’ve imagined that the air is a kind of swaddling so that the air held them in a kind of comfort.”

Making the first works: “It was a difficult process partly because you have to look very hard at the images to get the detail to elicit empathy from your viewer. I used the perspective of the photographer – either from the pavements looking up or from the buildings looking down. I’ve materialised the sky [in the wood] – It’s a symbolic arresting of the fall. I’ve imagined that the air is a kind of swaddling so that the air held them in a kind of comfort.”

The denial of identity to the victims: “That’s the fundamental problem. As a contrast, in the Orlando killings one the first things people did was read out the names [of the victims]. By having a name that allows us to mourn. With these people it wasn’t possible. We can’t mourn by biography. There can’t be mourning as individuals. It’s a kind of mourning in a general way.”

It’s not just about death: “In each area [of the exhibition] we’ve juxtaposed images of love. So as much as the exhibition is a process of mourning it’s also a defiance and an assertion of love. We have to assert this, we can’t just think of this process of mourning; the process of loving has to carry on. But the process of loving in those circumstances is a very difficult one.”

The propagandistic aim of the killings: “One of the first things that one has to think about when dealing with these images is, ‘do I perpetuate their intention?’ And I hope I haven’t, but you have to consider it. For that reason I didn’t make a video work, which was my first instinct. So I deliberately made things that are quiet and that are not photographic. Instead, I’ve used a physical [carved wood] image; one that is very slow to make. They are also slow to look at. There’s not that instant gratification of horror or pleasure, which violence gives to some people.”

On policing masculinity: “In the exhibition, part of what I’m speculating on is what kind of masculinity we have to adopt to survive in those kinds of circumstances. For some people it might be a disguise. For some people it might be enacting persecution… picking up a stone. If you’re in a society of corrosive masculinity and you’re made to witness this event, what do you do? How do you exist in that kind of society? We know the consequences of not conforming…”

On policing masculinity: “In the exhibition, part of what I’m speculating on is what kind of masculinity we have to adopt to survive in those kinds of circumstances. For some people it might be a disguise. For some people it might be enacting persecution… picking up a stone. If you’re in a society of corrosive masculinity and you’re made to witness this event, what do you do? How do you exist in that kind of society? We know the consequences of not conforming…”

Those in the crowds who threw stones: “The first thing [you think] when you see them is ‘these fucking shits’. You just hate these people. But after few months of working with the images, I had to think again about them. Yes they are shits, whether they were doing it so as not to stand out, or whatever, but I got a deeper understanding of possible motivations for their actions. We’ve all participated in coercive social practices. ”

The silence of the media: “I’ve given lectures about this work in America and in Italy and here, and it’s extraordinary to me how few people knew about these killings. People knew about the political killings but people didn’t know about the killings of the gay men. And that’s interesting. Who reports this? What deaths are reported, what deaths are recorded?”

It’s easier to rebuild ruins: “When Isis left [the ancient city of] Palmyra – at the same time [as the killings] Isis was destroying Palmyra and other historic sites – there was this rush by international governments offering to restore the ruins. And that seemed to me to be in some ways a good act but in many ways also an act of cowardice because it’s not acknowledging what Isis has been doing in terms of human lives. You can restore a column, you can restore a temple, but there was no acknowledgment of the failure of governments to speak about [these murders]. And we have to ask ourselves why.”

Choosing the subject matter: “As an artist and as a gay man, my identification is with these men. Of course, it doesn’t mean that my empathy doesn’t flow to the other victims of Isis. The responsibility that I can take is for this particular group of people. I don’t think that empathy should be bound by national borders. Identification is not necessarily determined by nationality but by affinities that go beyond nationality. Our empathy is defined to some extent by our experience; that gives authenticity and depth to our response.”

Choosing the subject matter: “As an artist and as a gay man, my identification is with these men. Of course, it doesn’t mean that my empathy doesn’t flow to the other victims of Isis. The responsibility that I can take is for this particular group of people. I don’t think that empathy should be bound by national borders. Identification is not necessarily determined by nationality but by affinities that go beyond nationality. Our empathy is defined to some extent by our experience; that gives authenticity and depth to our response.”

A South African context: “This a particularly spectacular and brutal method of killing gay people but we mustn’t think that we are free of prejudice in this country. Our Constitution gives us comfort in a legal sense but on the ground there is prejudice all the time. And the most obvious and most visible prejudice is against black women – which Zanele Muholi documents really diligently and well. I’m hoping that while this subject is inspired by particular events that this [work] is an echo of other bigotry and prejudice, which are pretty widespread.”

A Pile of Stones is on exhibition at the Goodman Gallery in Rosebank, Johannesburg until 15 February 2017.

Leave a Reply