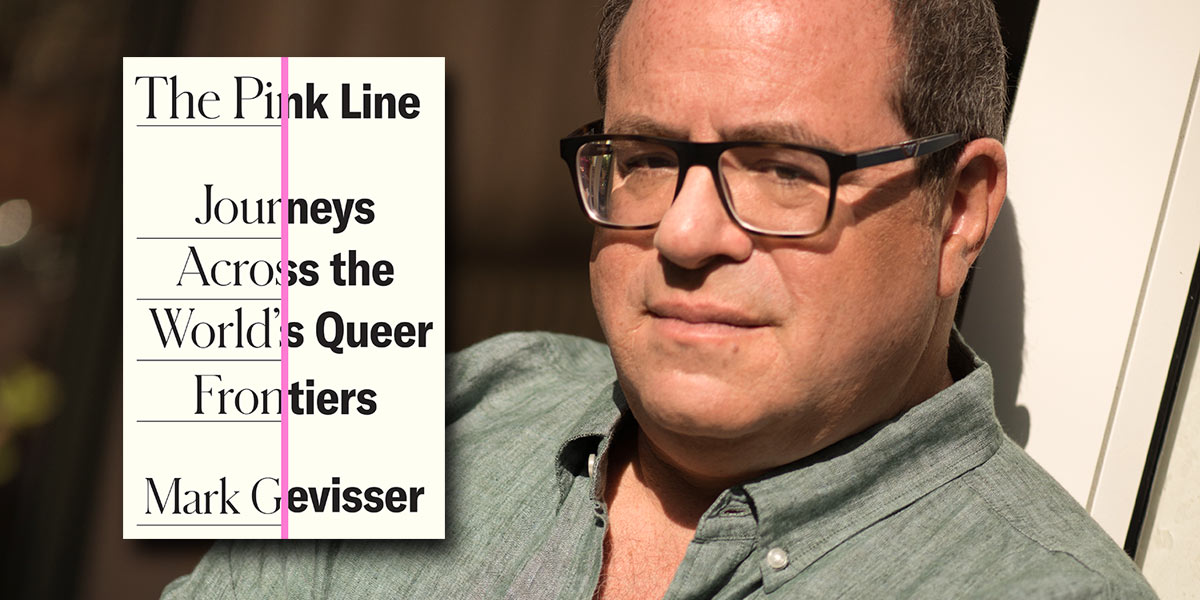

Queer books: The Pink Line by Mark Gevisser (extract)

Mark Gevisser, author of The Pink Line

Six years in the making, The Pink Line by Mark Gevisser follows individuals from nine countries to explore how “LGBT rights” became one of the world’s new human rights frontiers.

From refugees in South Africa to activists in Egypt, transgender women in Russia and transitioning teens in the American MidWest, The Pink Line folds intimate and deeply affecting stories of individuals, families and communities into a definitive account of how the world has changed, so dramatically, in just a decade.

Gevisser’s previous books include the award-winning Thabo Mbeki: A Dream Deferred. He writes frequently for The Guardian and The New York Times, and many other publications. Now based in Cape Town, he helped organise South Africa’s first Pride March in 1990, and has worked on queer themes ever since, as a journalist, film-maker and curator.

Below is Michael’s Story, an excerpt from The Pink Line.

After my meeting with Michael Bashaija in July 2015, I dropped him on the Ngong Road to get a matatu back to Rongai, where he lived in a communal house with twenty other Ugandan LGBT refugees, all of whom had fled across the border to Kenya. I watched him tuck his luxurious braids back into his woolen red beanie and maneuver his slight frame, rendered even skinnier by his tight green jeans, into the rhythm of the street. He arranged his eloquent features into a blank mask of maleness and disappeared into Nairobi’s rush-hour throng.

A few hours earlier, I had watched Michael pull the beanie off and shake out the braids, parted in a line along the top of his crown so that they fell down the sides of his head and made a heart of his fine-boned face. I had not seen him in a year, and I noted immediately how he was both more feminine and more assertive than the shy eighteen-year-old I had met in Kampala a year previously. There was something in his manner, even in the way he threw his tote bag down in rage and frustration, that told me he had stepped into himself.

Michael had come to meet me straight from the offices of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, where he had needed to get new documentation: his papers had been torn up by Kenyan policemen when he had refused to pay a bribe. At first, he told me, the guards at the UNHCR had mocked him and denied him access: “You Ugandans are bringing sin to Kenya!” Finally he had been granted access, but when his new papers were issued he was told he would have to repeat the refugee-eligibility interview he had done a few weeks previously.

This had thrown him into a panic. “They don’t believe me, that I’m a real LGBTI,” he said as we met, dissolving into tears. “I know it. They must think I’m one of the fraudsters. Or maybe they are punishing me because I was part of that protest [against UNHCR].”

I had first met Michael in Kampala, the Ugandan capital, in June 2014, the day before he was to go to court to testify against the man who had entrapped him via Facebook, extorted him, beat him up, and tortured him sexually. The attack had happened the previous February, just after Uganda’s president, Yoweri Museveni, had signed the country’s Anti-Homosexuality Act into law. Although the death penalty had been withdrawn for what was called “aggravated homosexuality”—having sex with minors or while infected with HIV—life imprisonment remained the mandatory sentence for anyone who “touches another person with the intention of committing the act of homosexuality.” This had led to a rash of extortion rackets. Michael was not the only victim, but he was the only one willing to take action. After he escaped, he went to the police.

From the very beginning, I had been struck by how carefully and thoughtfully Michael spoke, given that English was not his first language and that he had been out of school for two years. In Kampala, he had told his story dispassionately, as if he were looking at his violated self from far away. But now, in Kenya, he was different, aggrieved and anxious. Without a successful refugee-eligibility interview, he could not move forward: he could not get an Alien Card from the Kenyan authorities, which would give him more protection and enable him to work and begin the process of applying for resettlement in the United States. “I don’t think I can make it here. Let me go back to Uganda to die.” It was a teenager’s plea, a threat, a cry for help. “It’s better than staying here. Nobody cares for me here.”

MICHAEL HAD FLED Uganda six months previously, one of about seventy Ugandans claiming asylum on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity in December 2014, an all-time high. He was registered, housed in a transit center for a few days, and given 12,000 Kenyan shillings ($120). He went off to find a friend he had made contact with, and who had invited him to share a room near the airport.

A week later, on Christmas Day, while shopping for the festive meal, Michael was shoved by three men: “Why you acting like a girl?” They threw him to the ground and kicked him. He returned home with bruises and a swollen eye, horrified that no one had intervened to help him. The words of his assailants haunted him, in the way they sliced through his fantasies of the security that asylum would bring: “Museveni chased you from your country, and now you’ve come here, also to spoil it.”

Michael moved to a building in a more central district, where several other refugees lived. A few weeks later, he was arrested in a police raid on the building after neighbors lodged a complaint about a raucous party. He and thirty-four other Ugandans were taken to holding cells at the local police station, where Michael was roughed up by the cops when he was found to have concealed a cell phone with which he was trying to call for help. After twenty-four hours inside, he suffered a panic attack and passed out; he was taken to a hospital, and when he was discharged he learned that he and his fellow refugees had all been evicted from their lodgings. With not enough funds in the middle of the month to find a new place to live, the released refugees gathered at the UNHCR’s offices but were denied entry. They staged a protest at the compound gates, sleeping there over three nights. When the group engaged in what the UNHCR described as “violent behaviour,” the agency felt compelled to call the Kenyan police to disperse them. An enlightened Ugandan Catholic priest living in Nairobi, Father Anthony Musaala, stepped in. He rented two properties in Rongai and called these “the Ark Communes”; here he gave shelter to Michael and the others.

This is where Michael was living when I traveled to Kenya to meet him in July 2015.

TO GET TO THE ARK COMMUNES, I had to drive twenty kilometers out of Nairobi and through the town of Rongai before turning off at a local bar to bump down a steep dirt track that deposited me at a steel gate, set in a high cinder-block wall. Behind the gate was a large old settler house; there was a netball pitch cleared in the dust (the Ark team apparently competed in local tournaments) and a shabby couch on the veranda, leaking its upholstery. I would later be interviewed on this couch for “Ark TV” by a kid named Kenneth who had been a “radio personality” in Kampala before being forced to flee; he would do the job in a snappy navy blazer and pair of retro frames with no lenses, filmed by another communard with a smartphone.

The house had no running water or oven—cooking was done on an open fire—and a few pieces of mismatched furniture scattered about the common areas. A chart of officials was neatly tacked up: the “President” was Father Anthony, the Ark founder; there was also a “Chief Justice” and a “Minister for Ethics and Integrity,” a dig at the Ugandan ministry of the same name, responsible for leading the official anti-gay campaign back home. Michael—at nineteen the youngest resident—was “Deputy Minister for Education”; his job was to seek out training opportunities, and he and two others had recently enrolled in a computer course but had dropped out due to lack of funds.

Also posted on the entryway wall was a daily schedule and a set of injunctions: “Be Clean and Orderly!”; “Be Friendly and Hospitable!”; “Be Enterprising!” (twice); “Be Happy!” A table of “Rules and Regulations” listed the punishments for various infractions: a fine of five hundred Kenyan shillings for not maintaining “self-discipline and presentability at all times”; a fine of having to fetch five jerry cans of water from the village communal well for spending the night in someone else’s bed without official permission.

At the time I visited, there were around twenty residents, some sharing bedrooms, some in the partitioned double garage or burrowed into outdoor storerooms. A few rooms had signs of more permanent settlement—carefully made curtain-dividers, photos on a mantelpiece, neat racks of clothing—but most reflected the transience of their inhabitants. Michael’s room, a pantry off the kitchen, was dark and sparse: there was a mattress on the floor, and a padlocked duffel bag beside it. I had brought provisions, and as Michael’s boyfriend Pius supervised a lunch team, the other residents gathered in the communal area to tell me about their lives.

Tony, the laconic matinee-idol director of the Ark’s dance troupe, had collapsed recently due to the high blood pressure condition he could not afford to treat, but had fled the hospital when the attending doctor realized he was gay and threatened to call the police. Alex was an anxious older man who had been one of the first Ugandans to seek refuge in Kenya, and had endured hell in the Kakuma refugee camp in the desert up on the Ethiopian border: he was despondent because the United States had denied him resettlement on the grounds of credibility. Yasin, an articulate professional in his thirties, was one of the more recent arrivals: he had been forced to leave his place of residence a week previously, when it had been surrounded by a mob who had discovered the residents were homosexuals. The village chief and local police commander had come to the refugees’ aid, but it was not possible, of course, to return.

Here in Rongai, as well, the Ark Communes had begun to arouse the suspicions of the neighbors. In response to the terrorist attacks of 2014 and the influx of Somali refugees from the north, the Kenyan government had initiated a program called Usalama Watch: all Kenyans were to become acquainted with their neighbors, and to report anyone they did not know, or found suspicious. Inevitably, this triggered xenophobia, and made life even more difficult for the Ugandan refugees, too. A complaint had been lodged with the authorities in Rongai about these “strangers” living at the house, and the local police had come to investigate. The residents had insisted they were political refugees, as they had been coached to do by the UNHCR, but neither the neighbors nor the authorities were convinced.

This dissembling created an almost impossible dilemma. “We are told to be on the down-low and even lie about why we are here,” Michael said. “But we’re also told we need to integrate into Kenyan society and be enterprising so we can support ourselves. How is it possible to do both?”

The group was still smarting from a communication issued by the UNHCR’s Nairobi office a few weeks previously: “It is essential for LGBTI persons in Kenya to act in an inconspicuous and discreet manner for their own security . . . It is therefore of utmost importance that applicants keep a low profile.” Michael said that he was trying hard not to “gay it up.” But, he said, repeating a maxim that the refugees had taken on as some kind of motto, “Nature obeys no law.”

Many felt that being in Kenya put more constraints on them than living in Uganda. Back home, they knew the lay of the land and could negotiate it. “I’ve changed the way I dress completely,” Kenneth told me. “I’ve cut my hair, I’ve taken out all my pins [piercings]. In the world I look as if a man. But I will not say I keep a low profile in speaking and movements. It is imbued in me. I’ve tried, I’ve really tried, but even when I dress like this, people think me girly.”

Did he dress more flamboyantly back home in Kampala?

“Of course! Over there, we were much more swaggerlistic!”

Michael’s mentor at the communal house was in his early forties, a primary school teacher named Robert, known universally as Changeable, fired when his sexuality had been revealed. “Michael is my daughter,” Changeable told me. “Since he has come to Nairobi, he is so much more comfortable with himself. He is realizing that he is not just gay, but actually transgender. That is why he gets slapped so often in the streets. For walking girly.”

Michael seemed to agree with this assessment, although not, it seemed to me, with much conviction. Anyway, this would have to wait until he was resettled in America—he was dead set on being placed in the U.S.—he told me. For now, he needed to hold his femininity in check if he was going to survive.

Why, then, did he get the braids?

“I did it because, huh! I just felt I needed to be myself. In Uganda there were rules, but here I’m independent. No one can tell me, ‘Don’t do this, don’t dress like that, Michael, don’t braid your hair.’”

Michael needed the braids, and he needed the beanie: the former as part of his process of self-actualization and the latter to keep that very process in check, given where he found himself. It would be a difficult balancing act for anyone to maintain, let alone an impetuous nineteen-year-old just discovering his agency in the world. He had left Uganda on a journey toward being himself, after a violent and oppressive adolescence where his very survival was at risk because of who he was. His crossing the border to Kenya was the first step toward this imagined freedom, to the life that he believed awaited him in the United States. And he was living with a group of other people with exactly the same expectations. How, in such a context, do you temper such expectation? How do you gather up your hope, particularly after such abjection, and pile it back into the beanie?

The Pink Line is published by Jonathan Ball Publishers. The recommended selling price is R280.

Leave a Reply