New antibody therapy shows promise in fighting HIV

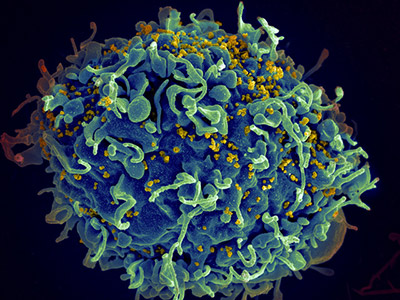

HIV particles infecting a human T cell (Image: NIH)

Researchers have shown that a new experimental therapy can dramatically reduce the amount of HIV present in a patient’s blood.

The results stem from HIV patient trials of a new generation of so-called broadly neutralizing antibodies, conducted by Rockefeller University researchers in New York.

The work, reported this week in Nature, brings fresh optimism to the field of HIV immunotherapy and suggests new strategies for fighting or even preventing HIV infection, they said.

Fighting HIV has always been difficult because the virus constantly mutates in the body to avoid being eradicated by the immune system. The new study, conducted in Michel Nussenzweig’s Laboratory of Molecular Immunology, found that a potent antibody, called 3BNC117, can catch HIV off guard and reduce viral loads.

“What’s special about these antibodies is that they have activity against over 80 percent of HIV strains and they are extremely potent,” said Marina Caskey, assistant professor of clinical investigation in the Nussenzweig lab and co-first author of the study.

Broadly neutralizing antibodies are produced naturally in some 10 to 30 percent of people with HIV, but only after several years of infection. By that time the virus in their bodies has usually evolved to escape even these powerful antibodies.

However, by isolating and then cloning these antibodies, researchers are able to harness them as therapeutic agents against HIV infections that have had less time to prepare.

In the study, uninfected and HIV-infected individuals were intravenously given a single dose of the antibody and monitored for 56 days. At the highest dosage level all eight infected individuals treated showed up to 300-fold decreases in the amount of virus measured in their blood.

This is the first time that the new generation of HIV antibodies has been tested in humans. In half of the individuals receiving the highest dose, viral loads remained below starting levels even at the end of the eight-week study period and resistance to 3BNC117 did not occur.

Researchers also believe that antibodies may be able to enhance the patient’s immune responses against HIV, which can in turn lead to better control of the infection. In addition, antibodies like 3BNC117 may be able to kill viruses hidden in infected cells, which serve as viral reservoirs inaccessible to current antiretroviral drugs.

Most likely, 3BNC117, like other anti-retrovirals, will need to be used in combination with other antibodies or antiretroviral drugs to keep infections under control. “One antibody alone, like one drug alone, will not be sufficient to suppress viral load for a long time because resistance will arise,” said Caskey.

One important benefit is the dosing schedule: an antibody therapy for HIV might require treatment just once every few months, compared to daily regimens of antiretroviral drugs that are now the front-line treatment for HIV.

Leave a Reply